Why most brands need nurturing, not heroics

“What sounds heroic on a CV is not always what a brand most needs. Brands don’t always require heroes; they don’t always respond to ‘alpha marketing’,” writes Helen Edwards in another of her excellent Campaign columns here. She suggests that marketing directors have a potentially dangerous tendency to try and ‘make their mark’ with big, bold marketing which is not always in the brand’s best interest.

Below I look at why this sort of alpha marketing happens and what the alternatives are.

1. Short term roles = radical solutions

Helen points the finger of blame for overly-radical alpha marketing at the relatively short tenure of marketing directors, an issue we posted on back in 2011 here, quoting results from our brand leadership research. The majority of our CMO research panel said that marketing directors needed three years or more to make a true impact. However, only 34% of CMOs stick around this long or more, down from 41% in 2015, according to research from Spencer Stuart quoted here.

With this short tenure comes the temptation “to go for a full brand repositioning when a brand refresh would have been the saner course,” suggests Helen. A short term CMO needs to make a big splash to be able to “move briskly upwards from one brief stint to the next.” But pushing the repositioning button is a radical and highly risky option, as Helen rightly points out. Lucozade is an often quoted but rare example of where such a repositioning has paid off.

Repositioning means trying to break the ‘memory structure’ that people have about a brand, ‘re-wiring’ their brains to think about it in a radically different way. And the chances of this working are slim, as I posted on here using as an example Wal-Mart’s flawed attempt to re-position itself as a more aspirational brand. The brand signed endorsement deals with Destiny’s Child and country singer Garth Brooks, ran an eight-page ad campaign in US Vogue, had a runway show at New York Fashion Week and started selling $500 bottles of wine and expensive jewelry. However, in trying to become more aspirational Wal-Mart forgot what made it famous and the re-positioning lacked credibility.

Of course, given the short-term stay of many CMOs, they take the risky option of repositioning safe in the knowledge that they “don’t stay around long enough to have to glue back the fragments shattered by the law of unintended consequences,” as Helen points out.

2. Refreshment beats repositioning

I agree wholeheartedly with Helen when she says, “Brand refresh looks less dramatic on the résumé but is usually the more justified option in reality.” Why? Because brand refreshment, or brand revitalisation as I tend to call it, builds on the memory structure that people have about a brand, rather than trying to change it completely. “The brand stays true to its long-term meaning but makes changes in the way these are expressed that are sufficient to jolt consumers, employees and the trade into positive reappraisal.”

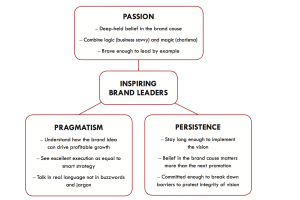

Brand revitalisation requires a different type of brand leader, with our research highlighting three key qualities:

Pragmatism: focusing ruthlessly on those changes in consumer behaviour that can really benefit the bottom line. If the best thing for the business is to build on what their predecessors did, then they do this rather than going for a radical change to make their mark. They are happy to be what Helen describes as, “A marketer who minimised risk and achieved steady gains.”

Passion: a real passion about and belief in the brand cause they are championing, even if this is a long-term brand purpose they inherited. “The ones willing to build on the work of others rather than bury it, respect brand heritage rather than disown it, and refresh the organisation’s most precious asset rather than reinvent it,” as Helen calls them.

Persistence: True brand leaders stick around long enough to not only create a vision, but also to implement it and drive it through the organisation.

3. Remember and refresh what made you famous

The key to brand revitalisation it to look forward at the changes in society and competitive landscape and how you need to react to these AND to look back at what made the brand famous. The trick is to highlight the equities that are still relevant and give them a fresh twist. A key step is to assess the health of the category and the health of the brand to understand the required balance between freshness and consistency. For a sick brand in a declining category, a radical repositioning may in fact be needed. But in many cases a better route is to balance freshness and consistency.

Helen gives several different types brand refresh with examples for each:

- “Reinterpreting roots”: Burberry’s refocusing back on the classic trench, that we have posted on several times including this one here, leading to “a near-tripling of sales for Burberry”.

- “Relevance hike”: Mattel giving its Barbie doll some ethnic variety and modifications to her implausibly slender body, driving “double-digit growth for Barbie after ten quarters of decline“.

- “Raising the stakes”: brilliantly executed by Persil, which reinvigorated its tired “dirt is good” positioning by showing that today’s kids spend less time outdoors than prisoners, resulting in “a 12 million upsurge in washes for Persil.”

In conclusion, brands would benefit from having leaders who are focused on creating a long-term legacy rather than short term heroics. Take this route and you might miss out on the short-term ‘high’ of a radical repositioning. But the brand is likely to enjoy more sustainable growth and you will have a deeper, enduring sense of achievement.

We outline some practical tools to help you remember and refresh what made your brand famous in the new brandgym book that you can pre-order here.