“If a brand really wants to make a difference, surely there is a responsibility to do more than simply highlight an issue?” asks Martin Finn in a Campaign column here. He uses as an example Dove’s Self Esteem Project, whose workshops have reached 43,000 school kids in the past year.

But should brands really be trying to solve society’s problems like this? Does moving from “traditional marketing to focussing instead on trying to bring about actual change,” as Martin suggests, make business sense?

1. Don’t mix up ‘brand purpose’ and ‘social mission’

There is a tendency to think that purpose and social mission are the same thing, as this article proposes. However, these are two different things. Most brands can benefit from having a sense of purpose, that we define as ‘The positive and distinctive role a brand plays in improving everyday life.’ This goes beyond the purely functional to appear to the head, but also the heart. But brand purpose does not have to mean solving society’s problems.

Social responsibility can play a lead role in brand purpose, especially for corporate brands. The vision of Dove’s parent company, Unilever, is “To grow our business, while decoupling our environmental footprint and increasing our positive social impact.”

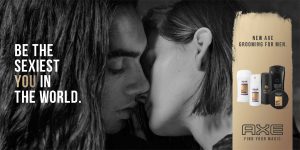

But social purpose can also play a supporting role, as part of how a brand delivers its purpose. Another Unilever brand, Axe, sharpened and updated its brand purpose to be ‘Helping guys celebrate their individuality and be as attractive as they can be’. This purpose remains anchored on making guys feel and smell good so they can form a loving, caring and respectful relationship with the woman of their dreams. Or something along those lines, at least. Becoming the official partner of CALM (Campaign Against Living Miserably) plays a supporting role.

2. Keep it real

Care is needed not to get carried away and ladder up so high that your brand of peanut butter or pet food is trying to deliver world peace, as beautifully illustrated in one of Tom Fishburne’s most famous cartoons below. Keeping things at a human, personal level is often a better route. “Marketers see purpose as the bigger picture, but people see it as what you do in daily life. Purpose isn’t necessarily about saving the planet. It doesn’t have to be worthy per se; it can be about taking small and meaningful actions,” observed Stephan Loerke, MD of the World Federation of Advertisers.

3. Sell more stuff

Let’s not forget that the ultimate purpose of purpose is to sell more stuff. The main role of manufacturers of soap, shampoo, margarine is not to change the world; we have NGOs, Charities and governments to do that. Back with Unilever, a recent Times article asked, “Should Persil Paul stick to selling washing powder?”, going on to observe that “Unilever’s CEO (Paul Poleman) has scored top marks for bolstering the consumer giant’s credentials for sustainability. But should the Dutchman be more worried about its flagging sales?”

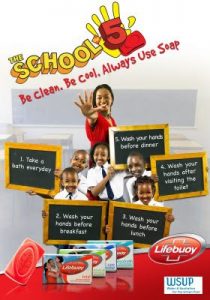

I suggest you keep your brand purpose rooted in the product category, like Lifebuoy soap. The brand’s purpose is ‘To create accessible hygiene products and promote healthy hygiene habits’, with the brand’s ‘Handwashing Behaviour Change Programme’ playing a central role in delivering against this. The ambition is to change the hygiene behaviour of 1 billion consumers across Asia, Africa and Latin America by using Lifebuoy to helps kills germs and prevent diarrhoea. This is great for society. But it also great for Unilever’s bottom line, as you would hope and expect a lot of these billion people to be new Lifebuoy consumers. Hell, check out the ad below: it suggests using Lifebuoy five times a day. That’s good hygiene, but also pretty hard selling to drive volume!

![]() In conclusion, I fully endorse Martin’s recommendation that, “Marketing with purpose about more than a hash tag and more than a viral video. Brands need to turn words into action.” Right on. However, I suggest solving society’s problems is only one way to do this, a way that Martin does have a vested interest in promoting by the way – the Dove workshops mentioned at the start of the post were devised by Martin’s company, EdComs.

In conclusion, I fully endorse Martin’s recommendation that, “Marketing with purpose about more than a hash tag and more than a viral video. Brands need to turn words into action.” Right on. However, I suggest solving society’s problems is only one way to do this, a way that Martin does have a vested interest in promoting by the way – the Dove workshops mentioned at the start of the post were devised by Martin’s company, EdComs.